...and here's the final half!

...and here's the final half!Lines are clearly drawn in the sand over whether violence portrayed in horror movies has a good or bad effect on its viewers; it seems as though either position comes down to a matter of taste. But is the aestheticization of violence in horror movies a less subjective concept? In regard to cinema, the term is used to explain the depiction of violence in a manner that is “stylistically excessive in a significant and sustained way” so audience members are able to connect references from the “play of images and signs” to artworks, genre conventions, cultural symbols and concepts (1). The way in which violence is aestheticized can be done in a number of ways.

Filmmakers can break up a scene into its components and depict it from different angles, then reassemble the parts. An editor can produce a non-realistic sequence of intercut, edited images, which forces the audience to interpret the images according to a set of semiotic rules. When a film director stages a scene, the audience may consider it less realistic; this is because the scenario is filtered through the filmmaker’s sensibilities and the outcome reflects the director’s motives. Hence, the lighting, make-up, costumes, acting methods, cutting and soundtrack music selection combine to inform the audience about the filmmaker’s intentions (1).

Over time, certain styles and conventions of shooting and editing are standardized within a medium or genre. Some conventions tend to naturalize content and make it seem more real. Other methods – which are quite popular in numerous subgenres of horror, including the slasher or giallo – breach convention to create an effect. In movies with aestheticized violence, the “standard realist modes of editing and cinematography are violated in order to spectacularize the action being played out on the screen;” directors use quick and awkward editing, canted framings, shock cuts and slow motion to emphasize the impacts of bullets or the “spurting of blood” (3).

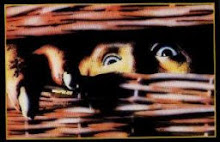

A perfect example of a highly stylized portrayal of explicit violence is in Italian horror director Dario Argento’s Suspiria (1977). The plot of the supernaturally charged giallo (the Italian word for “yellow,” used to describe the dustjackets of old pulp detective stories) deals with a coven of witches who control a German dance academy. The opening murder sequence showcases a woman being stabbed repeatedly – including once in the heart, shown in an extremely uncomfortable close-up – then subsequently hanged after her bloodied body crashes through a beautiful stained glass ceiling.

Xavier Mendik, the director of the Cult Film Archive at University College Northampton, describes the movie as “a film that requires contemplation. Its surreal compositions emulate the feel of an artist’s canvas, with individual scenes being more aesthetically pleasing than the film as a whole. In characteristic Argento style, [the opening murder] is saturated with primary colors and a near-hysterical soundtrack. Both of these features are so overpowering as to distract the viewer from the gory activities that the scene details. The unnerving force of the scene is once again testament to the director’s ability to manipulate every aspect of cinematic technology in his quest to expand the boundaries of horror cinema” (10).

So are these stylistic and artistic elements the reason why horror movies maintain such a firm grasp on moviegoers today, or is it something else completely different altogether? In his book, The Philosophy of Horror, or Paradoxes of the Heart, Noel Carroll attempts to answer this very question: “Why would anyone be interested in the genre to begin with? Why does the genre persist?” (4). He is puzzled by this, because Carroll says in the ordinary course of affairs, people shun what disgusts them: “We do not, for example, attempt to add some pleasure to a boring afternoon by opening the lid of a steamy trash can in order to savor its unwholesome stew of broken bits of meat, moldering fruits and vegetables, and noxious, unrecognizable clumps, riven thoroughly by all manner of crawling things” (4).

Carroll believes this to be the “paradox of horror.” Horror movies obviously attract consumers, but by means of the “expressly repulsive.” There is evidence showing the genre is pleasurable to its audience, but it does so by dealing with the sort of things that cause “disquiet, distress and displeasure.” The fundamental question then becomes: “Why are horror audiences attracted by what, typically [in everyday life], should [and would] repel them? How can horror audiences find pleasure in what by nature is distressful and unpleasant?” (4).

Jerrold Levinson attempts to summarize Carroll’s answers, and provide some of his own insight. Carroll offers everything from author H.P. Lovecraft’s belief that horror is valued for the quasi-religious cosmic awe it inspires, to Freudian explanations in terms of surrogate enactment of repressed psychosexual longings, and suggestions of Eaton and Feagin that satisfaction might reside in some sort of controlling meta-response to inherently unpleasant first-order reactions (7). However, Levinson says, “Carroll claims that our main interest and pleasure in horror fiction lies in its narrative structure, rather than directly in the monster’s horrific nature or our reaction to that. It is this curiosity, the desire for information, that drives the horror genre” (7). Daniel Shaw supports this statement, saying, “Curiosity is at the heart of most narratives; without the desire to know, the narrative flow would be un-involving” (13).

The nature of horror movies is merely a side effect for Carroll, “a side effect that is paid in order to reap the cognitive rewards of investigation, disclosure, and unmasking, and not the key to a more fundamental explanation of horror’s appeal. The monster is interesting, ultimately, only because it fascinates.” Levinson believes that while Carroll offers compelling arguments that support their relevance to aesthetic theory, a qualm, “that the account fails to locate the specific appeal of horror tales as opposed to ones of benevolent fantasy or marvelous categorical violation, stubbornly remains” (7). Shaw agrees, saying, “[Carroll] provides an ingenious solution to the paradox, but fails to come to grips with the essence of horror in the process” (13). It appears that this “specific appeal,” or the essence of horror, is left to be interpreted by the audience.

Horror cinema aficionados are left to wonder if there are numerous reasons or maybe no reason at all as to why excessively violent films are popular among moviegoers, past and present. Is it because people are impressed by the lighting and camera techniques combined with bloody special effects? Do they need to satisfy their morbid curiosity, and succumb to the fear of the unknown? Or, quite simply, do they just enjoy being scared out of their wits? Whatever the case may be, it is safe to say the horror genre is alive and will remain going strong. Regardless of whether critics think these films act as cathartic devices, or are extremely dangerous and detrimental to society, people will continue to be entertained and disturbed by the appeal of the horror movie.

1. “Aestheticization of violence.” Reference.com Encyclopedia. Lexico Publishing Group, LLC., 2006.

2. Broeske, P.H. “Killing is alive and well in Hollywood.” Los Angeles Times, p.19-22, Sept. 2, 1984.

3. Bruder, Margaret Ervin. “Aestheticizing Violence, or How To Do Things with Style.” Film Studies, Indiana University, Bloomington IN.

4. Carroll, Noel. The Philosophy of Horror, or Paradoxes of the Heart, p.158-160. New York: Routledge, Chapman and Hall, 1990.

5. “Catharsis.” Dictionary of the History of Ideas. University of Virginia Library: The Gale Group, 2003.

6. Griswold, Charles. “Plato on Rhetoric and Poetry.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2003.

7. Levinson, Jerrold. “The Philosophy of Horror, Review.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 49 No. 3, p.253-258, Summer 1991.

8. Martin, Adrian. “The Offended Critic: Film Reviewing and Social Commentary.” Australian Quarterly, Vol. 72 Issue 2, April-May 2000.

9. Maslin, J. “Tired blood claims the horror film as a fresh victim.” New York Times, p.15, 23, Nov. 1, 1981.

10. Mendik, Xavier. “Dario Argento.” Senses of Cinema, November 2003.

11. Meyer, M. “Keeping a lid on gore and sex.” Video Magazine, p.75-76, March 1988.

12. Sapolsky, Barry S., and Molitor, Fred. “Sex and Violence in Slasher Films.” Mass Media and Society. Greenwich, CT: Ablex Publishing, 1997.

13. Shaw, Daniel. “A Humean Definition of Horror.” Film-Philosophy, Vol. 1 No. 4, August 1997.

No comments:

Post a Comment