Back in the fall of 2006, I took a Philosophy of Art course during my senior year of college. For my end-of-the-semester paper, I was able to focus it on my love of horror movies. It's probably my favorite non-journalism piece I wrote throughout my four years of higher education; plus, I was able to show my class the opening murders in Suspiria!

Back in the fall of 2006, I took a Philosophy of Art course during my senior year of college. For my end-of-the-semester paper, I was able to focus it on my love of horror movies. It's probably my favorite non-journalism piece I wrote throughout my four years of higher education; plus, I was able to show my class the opening murders in Suspiria!Due to the length of the paper, I split it into two parts. Look for part two (and my work cited) tomorrow!

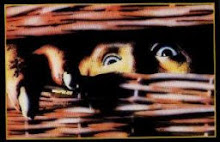

The Appeal of Murder in Style:

Aestheticization of Violence, Catharsis Theory and the Paradox of Horror Cinema

“If any human act evokes the aesthetic experience of the sublime, certainly it is the act of murder … if murder can be experienced aesthetically, the murderer can in turn be regarded as a kind of artist – a performance artist or anti-artist whose specialty is not creation but destruction.” – Joel Black, University of Georgia literature professor

“One of television’s greatest contributions is that it brought murder back into the home where it belongs. Seeing a murder on television can be good therapy. It can help work off one’s antagonism.” – Alfred Hitchcock, director of Psycho, The Birds

For almost a century, horror cinema has frightened, shocked and disgusted audiences with its portrayal of terrifying monsters, deranged serial killers with a bloodlust for young virgins, and other spooky things that go bump in the night. The question that has been asked for years is: why are these movies so popular? What is it about being scared and having the hair on the back of one’s neck stand straight up that keep people coming back for more? As horror movies become more and more socially acceptable in today’s culture, it is crucial to look at what makes these films attract mass appeal: plot, characters, tone, or perhaps most importantly, the aestheticization of violence. It is also important to ask: as a result of these films, are there any consequences to being fed a steady diet of severed eyeballs, guts and bloody aerial spray?

The origins of the mainstream horror movie began in the 1930s, with the release of such films as Dracula, Frankenstein and The Wolf Man. But while these classic Universal movie monsters provided big scares for their audiences, much of the violence was shown off-screen or largely implied. Although the commercial success of these movies was widespread, by the late 1940s the novelty began to wear off. Following the end of World War II, movie producers switched their focus to colossal insects and aliens from outer space. These films “appealed to the public because they vented fears of nuclear war and expressed a general mistrust of science and technology” (12).

The 1950s and 1960s ushered in a new element to horror cinema: color. The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) shocked moviegoers with its colorized blood and gore. H.G. Lewis, known as “the Godfather of Gore,” entered uncharted waters with 1963’s Blood Feast. The film’s main plot revolved around a man who stalks and mutilates beautiful young women. Lewis used the same formula in 2,000 Maniacs, The Gore Gore Girls, Color Me Blood Red and Wizard of Gore, single-handedly changing the face of horror with his full-color torture and murder scenes, which audiences loved (12).

As the decades passed, horror movies began to feature more and more explicit violence. The 1970s and 1980s delivered The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Dawn of the Dead, Halloween, Friday the 13th, Lucio Fulci’s The Beyond, and countless other gore epics. These movies had two major similarities: they were all huge financial hits, and they all featured impressive special effects involving extreme gore. With recent entries such as The Devil’s Rejects and Haute Tension, it is clear that these movies are still immensely popular in today’s culture, and more than half of the aforementioned titles in this paragraph have been remade in the past four years. So why does content that deals with such violent and disturbing subject matter appeal to mainstream audiences? Are there any far-reaching effects – positive or negative – because of this phenomenon?

When attempting to answer this question, it is important to look at the theories surrounding the effect of violence in mass media on society. Some critics say violence serves a “cathartic or dissipating effect ... providing acceptable outlets for anti-social impulses” (3). According to Adrian Martin, these “critics, who have regard – love, even – for violent cinema in its diverse forms ... have developed a ... response to those who decry everything from Taxi Driver to Terminator 2 as dehumanizing, desensitizing cultural influences.” They argue that “screen violence is not real violence, and should never be confused with it. Movie violence is fun, spectacle, make-believe; it’s dramatic metaphor, or a necessary catharsis akin to that provided by Jacobean theatre; it’s generic, pure sensation, pure fantasy. It has its own changing history, its codes, its precise aesthetic uses” (8).

This ideology is very similar to that of the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle. He supported a useful role for drama and tragedy: a way for people to purge their negative emotions. Aristotle mentions “catharsis” at the end of his Politics, which is the Greek word for “purgation, cleansing, and purification.” It is derived from katharein, meaning “to cleanse.” Aristotle says that after people listen to music that elicits pity and fear, they “are liable to become possessed” by these negative emotions. Afterwards, these people return to “a normal condition as if they had been medically treated and undergone a purge [catharsis] ... All experience a certain purge and pleasant relief. In the same manner cathartic melodies give innocent joy to men” (5).

At the opposite end of the spectrum, some critics see depictions of violence in films as superficial and exploitative. They argue that it causes audience members to become desensitized to brutality, and thereby increases aggressivity. One condemnation of the slasher movie subgenre (with such films as The Burning, My Bloody Valentine and Slaughter High) is the widely-held view that they single out women for injury and death. For example, a Los Angeles Times film critic claimed that the “brutal victimization of women [is] a recurring and obviously popular theme in such films” (2). During the ABC news show Nightline, correspondent Gail Harris summed up slasher films as “short on plot and long on brutality and violence, much of it sexual, almost all of it directed at women” (11). Film critics Gene Siskel and Robert Ebert also made similar claims on their television program Sneak Previews.

Slasher films have also been criticized for mixing excessive violence with sex. A New York Times film critic wrote that the violence in slasher films is “usually preceded by some sort of erotic prelude: footage of pretty young bodies in the shower, or teens changing into nighties for the slumber party, or anything that otherwise lulls the audience into a mildly sensual mood” (9). Daniel Linz and Edward Donnerstein have reported that slashers often include the mutilation of women in scenes that include sexual content. Many critics who claim that slasher films often portray sexual assaults believe combining erotic and violent scenes can be a direct cause for viewers, especially males, to associate sex with aggression in their everyday lives (12).

These opinions and beliefs echo the same words as the famous student of Socrates, Plato. He proposed to prohibit poets from his perfect society because Plato worried that their aesthetic ability to create attractive narratives about immoral behavior would corrupt young minds. Plato’s writings refer to poetry as a kind of rhetoric, whose “influence is pervasive and often harmful.” He believed poetry that was “unregulated by philosophy is a danger to soul and community.” He also warned that tragic poetry can produce “a disordered psychic regime or constitution” by inducing “a dream-like, uncritical state in which we lose ourselves in ... sorrow, grief, anger, [and] resentment.” In short, Plato argued that “What goes on in the theater, in your home, in your fantasy life, are connected” to what a person does in real life (6).

Stay tuned for part two tomorrow!

No comments:

Post a Comment